Science is a human enterprise

A few days ago Neil deGrasse Tyson tweeted a paean to Science that was widely panned.

He linked to this post in a follow-up tweet as a defense of his views. I’ll excerpt a lengthy bit from that piece and discuss several of the ideas further:

The scientific method, which underpins these achievements, can be summarized in one sentence, which is all about objectivity:

Do whatever it takes to avoid fooling yourself into thinking something is true that is not, or that something is not true that is.

This approach to knowing did not take root until early in the 17th century, shortly after the inventions of both the microscope and the telescope. The astronomer Galileo and philosopher Sir Francis Bacon agreed: conduct experiments to test your hypothesis and allocate your confidence in proportion to the strength of your evidence. Since then, we would further learn not to claim knowledge of a newly discovered truth until multiple researchers, and ultimately the majority of researchers, obtain results consistent with one another.

This code of conduct carries remarkable consequences. There’s no law against publishing wrong or biased results. But the cost to you for doing so is high. If your research is rechecked by colleagues, and nobody can duplicate your findings, the integrity of your future research will be held suspect. If you commit outright fraud, such as knowingly faking data, and subsequent researchers on the subject uncover this, the revelation will end your career.

It’s that simple.

This internal, self-regulating system within science may be unique among professions, and it does not require the public or the press or politicians to make it work. But watching the machinery operate may nonetheless fascinate you. Just observe the flow of research papers that grace the pages of peer reviewed scientific journals. This breeding ground of discovery is also, on occasion, a battlefield where scientific controversy is laid bare.

Science discovers objective truths. These are not established by any seated authority, nor by any single research paper. The press, in an effort to break a story, may mislead the public’s awareness of how science works by headlining a just-published scientific paper as “the truth,” perhaps also touting the academic pedigree of the authors. In fact, when drawn from the moving frontier, the truth has not yet been established, so research can land all over the place until experiments converge in one direction or another—or in no direction, itself usually indicating no phenomenon at all.

I understand why Neil - and so many others - share such vociferous faith in the scientific enterprise. Look around modern society and it is impossible not to see its fruits. We have ample empirical proof that humans are good at leveraging the scientific method to ignite progress. But, as Neil hints at in a few of my highlights, the reality of science is not as black and white as many make it out to be. It’s rarely a linear march toward The Great Understanding. A couple examples to illustrate:

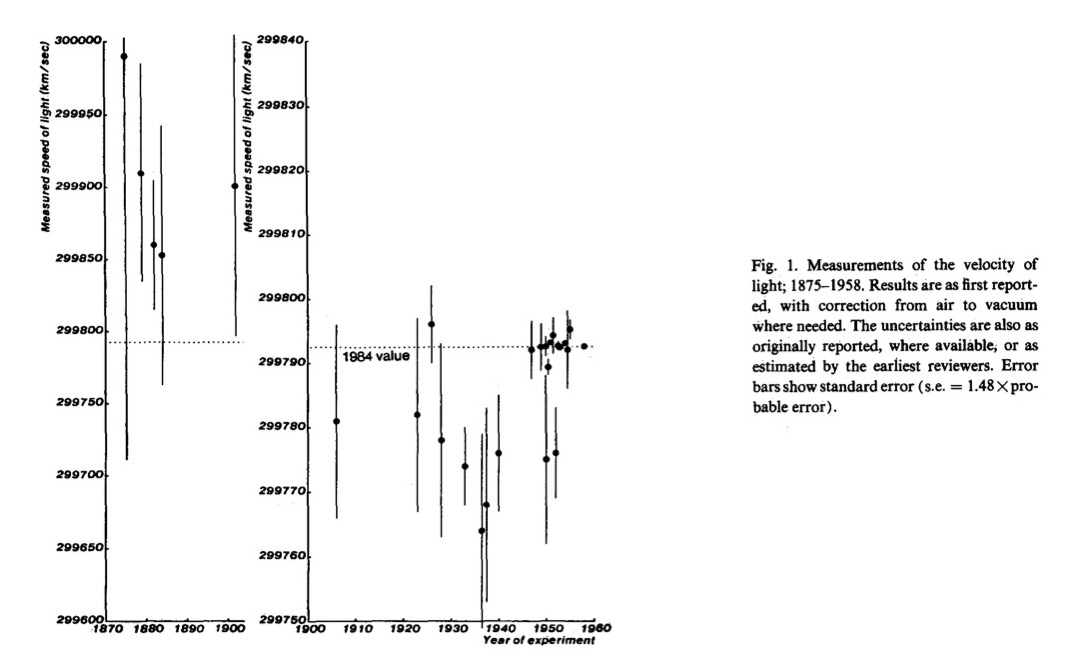

First, a paper which I did not appreciate enough when it was first introduced to me my first semester of graduate school is “On Uncertainty in Physical Constraints” by Henrion and Fischhoff (1985). The killer graph from the paper is below. It shows reported measurements of the speed of light, c, and associated error ranges for each measurement. Notice how the measurements cluster into 4 distinct groups. Prior to 1900 all the estimates were too high. In the early 1900s, the estimates were too low and from the 1920s to 1940s far too low.

Look also at the range on the error bars: only 6 of the 13 measurements prior to the late 1940s even had the true value within the standard error range. Instead, it’s clear the scientists were anchoring their estimates on those made by their predecessors. Rather than the popular narrative of scientists always striving for objective truth, we see evidence that scientists were hesitant to stray too far from previously erroneous estimates. This led to ongoing systemic error in estimation until the late 1940s.

Second is a paper from Azoulay et al titled “Does Science Advance One Funeral at a Time?” I will quote their paper directly to summarize their key findings (emphasis mine):

Specifically, we examine how the premature death of 452 eminent scientists alter the vitality (measured by publication rates and fund- ing flows) of subfields in which they actively published in the years immediately preceding their passing, compared to matched control subfields.

In contrast with prior work that focused on collaborators (Azoulay, Graff Zivin, and Wang 2010; Oettl 2012; Jaravel, Petkova, and Bell 2018; Mohnen 2018), our work leverages new tools to define scientific subfields which allows us to expand our focus to the response by scientists who may have similar intellectual interests with the deceased stars without ever collaborating with them.

To our surprise, it is not competitors from within a subfield who assume the mantle of leadership, but rather entrants from other fields who step in to fill the void created by a star’s absence. Importantly, this surge in contributions from outsiders draws upon a different scientific corpus and is disproportionately likely to be highly cited. Thus, consistent with the contention by Planck, the loss of a luminary provides an opportunity for fields to evolve in novel directions that advance the scientific frontier.

….

Indeed, most of the entry we see occurs in those fields that lost a star who was especially accomplished. Even in those fields that have lost a particularly bright star, entry can still be regulated by key collaborators left behind. We find suggestive evidence that this is true in fields that have coalesced around a narrow set of techniques or ideas or where collaboration networks are particularly tight-knit. We also find that entry is more anemic when key collaborators of the star are in positions that allow them to limit access to funding or publication outlets to those outside the club that once nucleated around the star.

The authors of this paper use a Planck quote about the death of scientists to motivate their work but I also think it’s a good example of what Kuhn called ‘scientific revolution.’ To paraphrase Kuhn: the accumulation of anomalies undermines an existing scientific paradigm and a new paradigm emerges to address the questions raised by those anomalies.

Azoulay et al provide empirical data for a mechanism by which paradigm change may occur: demographic change amongst the community of practitioners (e.g. the old guys die). What’s really important from Azoulay’s work is that the death of a superstar means entrants by scientists from ADJACENT fields - this is community change leading to paradigm change. However, as the authors show, that change in community can also be mediated by remaining practitioners if the networks are very tight knit.

Both of these papers provide examples of the fundamental truth of science: it is a human enterprise and progress is mediated by community dynamics. Science is not solely a method of inquiry, it is a body of knowledge amassed by a community of researchers each subject to human biases and fallacies. Science operates by community consensus and much of the error-checking mechanisms within science are subject to debates over who’s a member of the community and thus don’t act instantaneously.1 Science can be wrong for quite some time.

We will have this debate many more times in the years to come. “The science is clear” is a phrase we will hear uttered and it will require careful parsing. We can’t simply wield the authority “Science” as a cudgel to silence our opponents, which many are wont to do. Rather, one can accept the uncertainty inherent in science and invite good-faith debate without discrediting the enterprise. In fact, we must do so.

-

For the sake of clarity I leave aside the role of nefarious actors in influencing science. We have ample proof that both the tobacco industry and O&G industry poisoned the well of scientific knowledge in order to sow doubt on community consensus. My point here is even absent those mechanisms scientific discovery is not a linear process. It is certainly less so when politicized. ↩